Sjögren’s syndrome represents a significant diagnostic and therapeutic challenge, often masquerading as a collection of unrelated symptoms before its systemic, autoimmune nature is correctly identified. This chronic disease, characterized fundamentally by immune system dysfunction, extends far beyond the common presentation of dryness, impacting nearly every organ system and dramatically altering a patient’s quality of life. The core pathophysiology revolves around the misdirected activity of the body’s adaptive immune system, specifically a pronounced infiltration of lymphocytes into exocrine glands. This cellular siege progressively cripples the glands responsible for generating essential moisture—tears and saliva—but the true complexity of the disease lies in its capacity for multiorgan involvement and the inherent difficulty in capturing its protean manifestations under a single clinical umbrella.

Sjögren’s syndrome (also known as Sjögren’s disease) is a condition where the glands that produce fluid… stop working properly

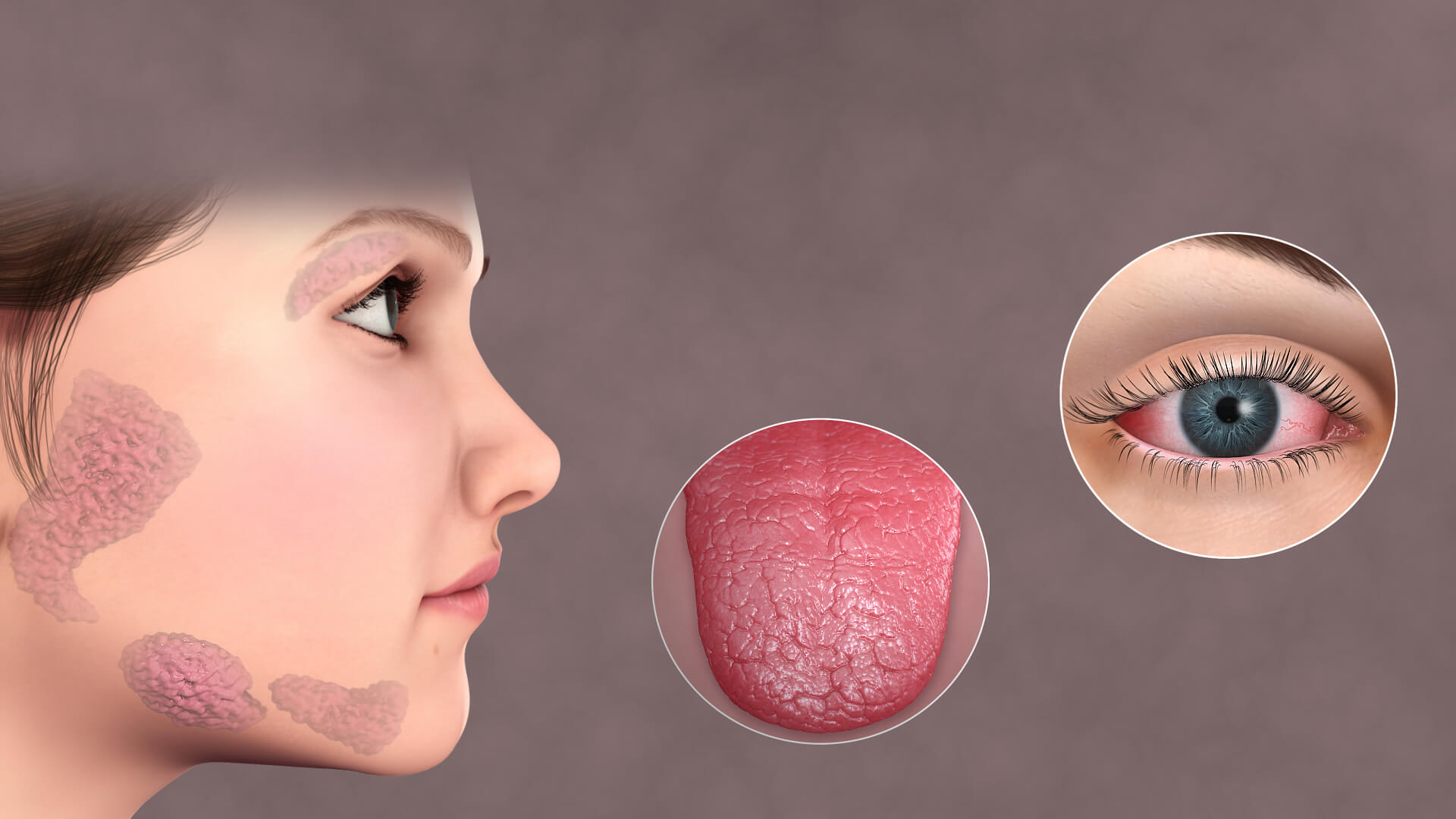

At its most recognizable, Sjögren’s syndrome is an exocrinopathy, a disease centered on the impaired function of exocrine glands. “Sjögren’s syndrome (also known as Sjögren’s disease) is a condition where the glands that produce fluid… stop working properly” succinctly summarizes the primary clinical picture. The lacrimal glands, which produce tears, and the major and minor salivary glands, which produce saliva, become the main targets of a sustained, destructive autoimmune attack. This immune assault involves a marked infiltration of white blood cells, predominantly T and B lymphocytes, which form dense, characteristic focal aggregates within the glandular tissue. This inflammatory microenvironment leads to progressive acinar and ductal cell damage, ultimately resulting in glandular fibrosis and atrophy. The cumulative effect is a severe, chronic reduction in tear production () and saliva production (

), manifesting as the hallmark sicca symptoms: a constant gritty, sandy sensation in the eyes and an unremitting feeling of cotton-mouth that impedes swallowing and speaking.

The classical triad of the disease that the vast majority of patients with SS exhibit is constituted by musculoskeletal pain, fatigue and dryness

While dryness defines the disease anatomically, the day-to-day experience of the patient is often dominated by symptoms that point to systemic inflammation and immunological overload. “The classical triad of the disease that the vast majority of patients with SS exhibit is constituted by musculoskeletal pain, fatigue and dryness” highlights the trio of symptoms that are most impactful on functional status. The dryness is only one dimension; the relentless, debilitating fatigue is a near-universal complaint, profoundly affecting professional, social, and personal life. This fatigue is often disproportionate to disease severity or physical exertion and is thought to be related to the underlying chronic inflammatory state and possible nervous system involvement. Concurrently, many patients contend with inflammatory polyarthritis or diffuse joint pain (), stiffness, and muscle aches (

). This combination of persistent pain and profound exhaustion makes it critically important to recognize Sjögren’s not merely as a localized dryness issue, but as a systemic inflammatory disease demanding a holistic management approach.

Up to 30–50% of patients with SS may show systemic disease

The disease’s capacity to extend beyond the exocrine glands and affect major organ systems underscores its systemic and serious nature. “Up to 30–50% of patients with SS may show systemic disease” is a critical piece of epidemiological information, emphasizing the risk of significant non-glandular complications. This extraglandular involvement is highly variable, affecting virtually any organ system, and can manifest as seemingly unrelated conditions. Pulmonary involvement can range from a chronic dry cough to potentially severe interstitial lung disease (). The kidneys can be targeted, commonly presenting as interstitial nephritis or distal renal tubular acidosis, which can disrupt the body’s acid-base balance and lead to electrolyte abnormalities. Neurological manifestations, including peripheral neuropathy—often presenting as numbness or tingling in the extremities—and central nervous system involvement (e.g., “brain fog” or cognitive dysfunction), further contribute to the complexity of the clinical picture, necessitating a broad-based, multi-specialty surveillance strategy.

Sjögren’s syndrome can be defined as primary or secondary, depending on whether it occurs alone or in association with other systemic autoimmune diseases

A further layer of diagnostic complexity is introduced by the distinction between the two forms of the syndrome. “Sjögren’s syndrome can be defined as primary or secondary, depending on whether it occurs alone or in association with other systemic autoimmune diseases” establishes this essential classification. Primary Sjögren’s syndrome () develops independently, not linked to any other pre-existing autoimmune condition, representing a standalone disease entity. Conversely, secondary Sjögren’s syndrome (

) occurs concurrently with another established autoimmune connective tissue disorder, most frequently rheumatoid arthritis (

) or systemic lupus erythematosus (

). This co-occurrence necessitates a differential diagnostic process, as the symptomatology may overlap and confound the clinical presentation. The presence of secondary Sjögren’s can often influence the overall disease trajectory and may potentially complicate treatment strategies, as therapeutic choices must address both the primary connective tissue disease and the associated

manifestations.

The diagnosis of Sjögren’s syndrome is based on characteristic clinical signs and symptoms, as well as on specific tests

Given the varied and often non-specific nature of its symptoms, the diagnosis of Sjögren’s syndrome is rarely straightforward and requires the integration of multiple data points. “The diagnosis of Sjögren’s syndrome is based on characteristic clinical signs and symptoms, as well as on specific tests” indicates the multi-pronged approach required. There is no single pathognomonic test, leading clinicians to rely on established classification criteria that weigh both subjective symptoms and objective evidence of glandular dysfunction and systemic autoimmunity. Key objective tests include the Schirmer test to quantify tear production and to measure salivary flow rate. Serological analysis for specific autoantibodies is also crucial, particularly the presence of

(

) and

(

), though their absence does not entirely exclude the diagnosis. The definitive, albeit invasive, confirmation often involves a minor salivary gland biopsy (labial gland biopsy) to check for the characteristic focal lymphocytic sialadenitis.

Sjögren’s can be challenging to recognize or diagnose because symptoms of Sjögren’s may mimic those of menopause, drug side effects, or medical conditions

The sheer non-specificity of early or mild symptoms contributes significantly to delays in diagnosis, which can often stretch for several years. “Sjögren’s can be challenging to recognize or diagnose because symptoms of Sjögren’s may mimic those of menopause, drug side effects, or medical conditions” speaks directly to the difficulty faced by clinicians, particularly outside of rheumatology. Common symptoms such as generalized fatigue, diffuse body aches, or simply having a dry mouth can be easily—and mistakenly—attributed to normal aging, pharmaceutical side effects (many common medications cause dryness), or other poorly defined conditions like chronic fatigue syndrome or fibromyalgia. This initial misattribution often results in patients being managed symptomatically by multiple specialists (e.g., ophthalmologists for dry eyes, dentists for recurrent dental decay), with the underlying systemic, autoimmune root of the problem remaining undiscovered until more severe, systemic manifestations emerge.

The hallmark clinical manifestations of SS are xerostomia (dry mouth) and keratoconjunctivitis (dry eyes)

Returning to the central glandular issues, the chronic lack of lubrication in the eyes and mouth gives rise to a spectrum of secondary complications that, while seemingly localized, severely impact quality of life and long-term health. “The hallmark clinical manifestations of SS are xerostomia (dry mouth) and keratoconjunctivitis (dry eyes)” serves as a reminder of the symptoms that patients must learn to manage daily. In the eyes, chronic dryness can lead to corneal epithelial damage, a foreign body sensation described as “sand or gravel,” and recurrent infections, all of which compromise vision. In the mouth, the protective, buffering, and antimicrobial properties of saliva are lost, leading to an alarmingly high rate of dental caries, periodontal disease, and recurrent oral candidiasis (thrush). The continuous management of these localized complications consumes a significant portion of the patient’s health burden, often requiring a complex regimen of artificial tears, saliva substitutes, and rigorous dental hygiene.

The most common complications of Sjogren’s syndrome involve your eyes and mouth

While the systemic complications carry the highest risk for mortality, the sheer frequency and persistent burden of localized issues related to dryness make them the most common sources of morbidity. “The most common complications of Sjogren’s syndrome involve your eyes and mouth” emphasizes that the chronic sequelae of sicca symptoms are not minor inconveniences. The accelerated tooth decay and the potential for corneal damage are tangible, irreversible consequences of unmanaged exocrine dysfunction. This necessitates a proactive approach where preventative strategies—like prescription fluoride treatments, constant hydration, and regular eye examinations—must be meticulously maintained to stave off these complications. Addressing these seemingly minor issues aggressively is a key component of long-term disease management, aimed at preserving both vision and dental integrity throughout the patient’s life.

Lymphomas develop in about 7.5% of SS patients, mostly marginal zone B-cell lymhomas

Perhaps the most serious and prognostically significant complication of primary Sjögren’s syndrome is the significantly elevated risk of developing lymphoid malignancies. “Lymphomas develop in about 7.5% of SS patients, mostly marginal zone B-cell lymhomas” highlights a critical aspect of patient surveillance. The chronic, sustained activation and proliferation of B lymphocytes, which characterizes the underlying autoimmune process, creates a pre-malignant state, markedly increasing the risk for non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphoma, particularly the extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma ( lymphoma), which often arises in the salivary glands. This elevated cancer risk underscores the fact that Sjögren’s is not just an inconvenience, but a genuine immunoproliferative disorder. Close monitoring for signs of lymphoma, such as rapidly or persistently enlarging salivary or lymph glands, is an essential, life-saving component of ongoing care for all individuals diagnosed with

.

There is no cure for the disease. Currently, treatment is divided into categories depending on the form of the disease

The current therapeutic landscape for Sjögren’s syndrome reflects the disease’s complexity and the absence of a curative intervention. “There is no cure for the disease. Currently, treatment is divided into categories depending on the form of the disease” sets the stage for a realistic management strategy. Treatment is fundamentally supportive and disease-modifying, targeting specific manifestations. Glandular dryness is typically managed with local measures like artificial tears and sialogogues (drugs that stimulate saliva production), while systemic involvement and high-risk features (e.g., vasculitis or significant organ damage) necessitate the use of immunosuppressive or immunomodulatory therapies, such as corticosteroids and specific biologic agents, to control the underlying autoimmune process. The heterogeneity of the disease means that management must be highly individualized, a constant negotiation between alleviating chronic discomfort and suppressing potentially destructive systemic inflammation, requiring a flexible, multi-specialty team approach to ensure comprehensive care.