The pervasive nature of tobacco smoking as an environmental factor means its influence stretches far beyond the commonly understood pulmonary and cardiovascular damage. Within the intricate landscape of autoimmune disorders, particularly those classified as rheumatic diseases, the relationship is not merely correlational; it is mechanistic, often acting as a key trigger that disrupts the delicate immunological balance. This disturbance can initiate disease development, accelerate its progression, and even fundamentally alter a patient’s response to therapeutic interventions. Understanding this complex interplay requires moving past the simple notion of smoking being “bad for you” and delving into the specific molecular and cellular pathways where tobacco’s toxic components wreak havoc on the immune system’s sense of self.

The Most Important Environmental Risk Factor to Be Extensively Studied and Widely Accepted

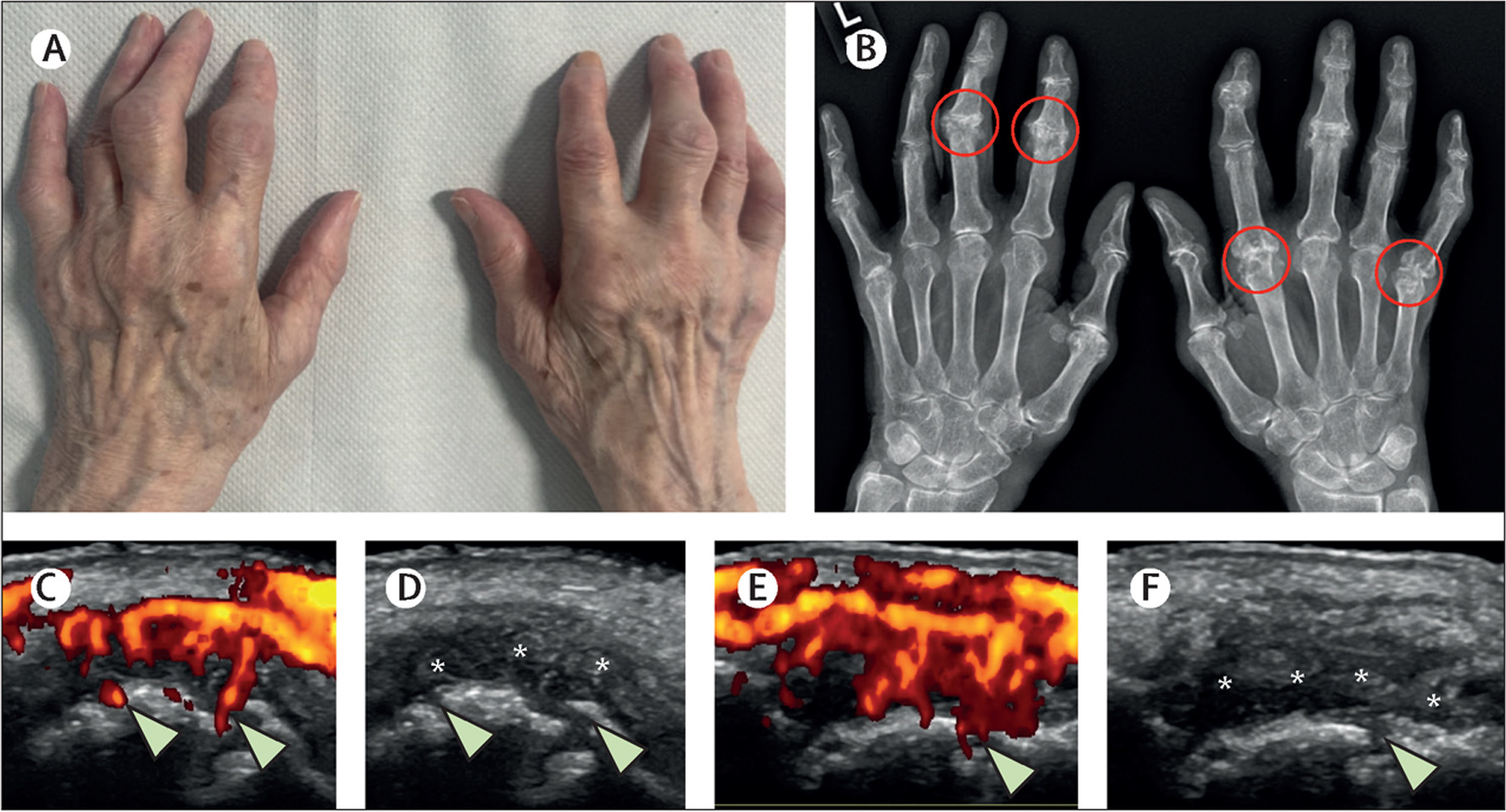

Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) presents the most extensively documented and compelling case for a direct causative link with tobacco. For decades, epidemiological studies have consistently identified smoking as the most important environmental risk factor to be extensively studied and widely accepted for RA development. The risk for smokers is often double that of non-smokers, with the probability rising significantly in a dose-dependent manner—meaning the more someone smokes, the higher their risk climbs. This is a crucial detail that moves the discussion beyond general risk to a quantifiable hazard. Furthermore, the persistence of this risk is notable; even after years of cessation, a former smoker’s likelihood of developing RA remains statistically elevated compared to someone who has never smoked, highlighting the long-lasting immunological signature left by tobacco exposure.

The risk of developing RA in smokers is known to be double that of non-smokers

The specific danger lies in the strong gene-environment interaction that has been revealed. Individuals who carry specific HLA-DRB1 alleles—genetic markers encoding the “shared epitope”—and also smoke face an especially compounded risk. This finding provides a powerful molecular context for how an external factor can interact with a pre-existing genetic vulnerability to manifest a chronic autoimmune disease. The shared epitope, when combined with smoking, is tied almost exclusively to a particular, highly aggressive form of the disease: anti-citrullinated protein antibody (ACPA)-positive RA. This distinction is critical because it separates a large subset of RA cases and points toward a specific pathogenic pathway involving citrullination.

Citrullination Has Been Reported to Be an Important Factor for the Development of RA

At the core of the smoking-RA link is a biochemical process known as citrullination. This is a post-translational modification where the amino acid arginine in a protein is converted into citrulline by the enzyme peptidylarginine deiminase (PAD). While this process is a normal part of cellular function, tobacco smoke inhalation—particularly within the lung’s mucosal tissues—is thought to upregulate the expression of this PAD enzyme. The numerous chemicals in cigarette smoke induce intense localized inflammation, especially in the lungs, which leads to the formation of abnormally large quantities of citrullinated proteins. The immune system, mistaking these newly altered proteins for foreign invaders, mounts an attack, generating ACPA.

Citrullination has been reported to be an important factor for the development of RA

The generation of ACPA is significant because these autoantibodies are highly specific to RA, often detectable in the blood years before the onset of clinical joint symptoms. This suggests that the process of autoimmunity itself—the misguided self-attack—is incubated in a remote location, like the lung, long before the joints become the target of the inflammatory response. Smoking, therefore, acts as a pivotal environmental trigger that essentially “breaks” the immune system’s self-tolerance via mucosal inflammation, initiating the production of the very autoantibodies that drive the chronic joint destruction characteristic of the disease. This is why the prevalence of smokers is significantly higher in the sub-group of patients with ACPA positive rheumatoid arthritis than in the ACPA-negative sub-group.

Smoking Has Been Connected to Cutaneous Symptoms, Damage Accrual, Including a Rapid Development of Kidney Failure

The detrimental reach of smoking extends beyond RA to other systemic autoimmune conditions, notably Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE). While the connection is considered somewhat less direct and absolute than the RA link, emerging evidence solidifies tobacco’s role as a potent exacerbating factor. Smoking has been connected to cutaneous symptoms, damage accrual, including a rapid development of kidney failure in those with Lupus Nephritis. Furthermore, smoking in SLE patients is associated with a higher likelihood of developing key autoantibodies, particularly anti-dsDNA antibodies, which are a strong indicator of disease activity and potential organ damage, especially to the kidneys.

Smoking has been connected to cutaneous symptoms, damage accrual, including a rapid development of kidney failure

The biological mechanism here involves the general pro-inflammatory and pro-oxidative stress effects of cigarette smoke, which can lead to increased DNA damage and promote the inefficient clearance of apoptotic cells. This failure to properly remove cellular debris, which contains nuclear antigens, can promote a loss of self-tolerance, providing the necessary material for the immune system to begin producing autoantibodies against the body’s own DNA. Current smoking, specifically, has been associated with higher Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI) scores, signifying a greater overall burden of disease activity. This indicates that for someone with lupus, continuing to smoke is not merely an inconvenience, but a genuine threat to the stability and long-term health of multiple organ systems.

Current Smokers with RA Don’t Respond as Well to Many RA Treatments

Perhaps one of the most disheartening aspects of the link between smoking and rheumatic disease is the impact on treatment efficacy. Even after a diagnosis has been established and therapeutic interventions have begun, smoking continues to undermine the patient’s recovery. Studies consistently show that current smokers with RA don’t respond as well to many RA treatments, particularly the advanced, targeted therapies known as biologics, such as TNF-alpha inhibitors. They are significantly less likely to achieve a state of remission or even a satisfactory low disease activity level compared to their non-smoking counterparts.

Current smokers with RA don’t respond as well to many RA treatments

This poor treatment response is a multi-faceted problem. It is speculated that the continuous high load of inflammatory mediators induced by smoking may simply overwhelm the therapeutic action of the medications. Furthermore, the chemical components of tobacco smoke might interfere with the drug’s metabolism or its direct molecular target within the immune cell pathways. The practical outcome is that patients who smoke often require higher doses of medication, experience more aggressive disease progression, and ultimately have a higher rate of irreversible joint damage and disability. This places smoking not just as a risk factor for onset, but as a major determinant of disease severity and long-term prognosis.

The Overall Risk of Developing Rheumatoid Arthritis Reduces Over Time

Despite the grim findings, the data on smoking cessation offers a powerful message of hope and a clear rationale for intervention. The studies have revealed that while the risk of developing RA remains high for a time even after quitting, the overall risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis reduces over time following cessation. Each passing year without tobacco moves the individual closer to the baseline risk of a never-smoker, even if the process takes many years—sometimes a decade or two—to fully normalize. For those already diagnosed with a rheumatic disease, quitting smoking has immediate, tangible benefits.

The overall risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis reduces over time

In patients with established RA, ceasing tobacco use is associated with a reduced disease activity and a better response to medication, improving the likelihood of achieving remission. The risk of all-cause mortality, which is elevated in RA patients, also decreases significantly within the first year after quitting. This evidence transforms smoking cessation from a general health recommendation into a critical, disease-modifying strategy specifically for the management of autoimmune rheumatic conditions. Addressing tobacco dependency is, therefore, an indispensable part of comprehensive rheumatological care, often having as profound an effect on disease outcomes as the potent pharmacological treatments themselves.